由于全国住房贷款过多,新南威尔士州购买已建房屋的新抵押贷款在两年内平均猛增了20多万澳币。担心正在增加,这种大比例向房地产注资的偏好,可能会损害澳大利亚的长期生活水平。

随着悉尼房价中位数每天攀升近850澳元,经济学家警告,未来工资增幅将降低,因为大量资金转成了砖块和砂浆,阻碍了对企业的投资或对改变生活的技术进步。

澳联储于2019年年中重新开始下调官方利率,以推动经济更快扩张,降低失业率,推动工资增长。去年冠状病毒大流行的到来迫使它降息至0.1%的历史低点,同时启动量化宽松计划,向金融体系注资逾2000亿澳元。

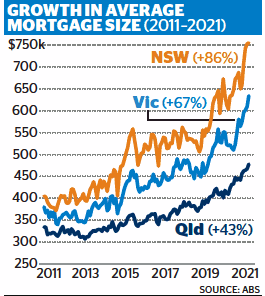

自开始降息以来,新南威尔士州购买已建房屋的平均抵押贷款从近55.4万澳元跃升至7月份创纪录的75.5万澳元,两年内增长了36%。

在此期间,每个州和领地的平均抵押贷款都有增长。在维多利亚州,该指数上升了三分之一,至63.4万澳元;在堪培拉,该指数上升了28%,至57.5万澳元;昆士兰州则上升了22%,目前为47.8万澳元。

抵押贷款的增加是应对房价飙升必然的产物,尤其是自去年年中以来。

悉尼的别墅中位数现在是130万,在过去12个月里上涨了30.8万,即每天上涨843澳元。根据CoreLogic的数据,墨尔本的别墅中位数在过去一年里每天上涨473澳元之后,现在为95.5万。

房价的大幅上涨,导致银行目前投放给自住者和投资者的抵押贷款,达到创纪录的1.9万亿澳元。其中在短短两年内,对自住者的贷款增加了1450亿美元。

正是由于抵押贷款的飞速增加,海量资金灌入到房地产市场,让经济学家们感到担忧。

RBC Capital Markets的董事总经理Su-Lin Ong表示,大量资本正被投入住房市场,而不是通过低利率、政府激励措施和税收制度来提高生产率。她说,虽然建筑业是经济的重要组成部分,但它雇佣的人数远不如专业和科学部门。

银行发现,将数十万资金交给人们购买现有房屋,而不是将其投入新业务领域,这样做要安全得多,也更加容易。

你可以在应用程序上就能申请住房贷款,但是对于一个中小企业来说,想获得贷款要比这困难一百倍。从银行的角度来看,前者是一个更安全的贷款渠道,而向企业放贷的风险要高得多。

Su-Lin Ong表示,如果将更多资金投入研发或创新型公司,将给国家带来长期利益。但这里有一个简单的机会成本问题。这就是我们为什么不这么做的原因。

今年早些时候,作为各国中央银行的中央银行,国际清算银行(BIS)发布的研究报告显示,尽管高房价通过提高家庭消费在短期内提振了经济活动,但长期生产率实际上更低。

在澳大利亚,今年早些时候,生产力委员会Productivity Commission发现,到2020年的十年间,生产率增长已降至60年来的最低点。

宏观经济咨询公司Macroeconomics Advisory首席经济学家斯蒂芬·安东尼Stephen Anthony说,没有生产率的提高,所有澳大利亚人都会受到不良影响。“如果想提高生活水平,如果想提高工资,那么需要提高生产率来实现。”

安东尼认为,无论是澳大利亚还是整个发达国家,住房已经成为一个由央行和政府支持的庞氏骗局。

他说,在货币政策完全用尽之后,各国政府不得不加大力度,制定适当的政策,奖励承担冒险,确保所有开支的使用都需着眼于效率。

原文如下:

House values soar $850 a day amid fear for living standards

The average new mortgage to buy an established house in NSW has soared by more than $200,000 in two years amid a nationwide glut of home lending, raising fears our obsession with pumping money into real estate may hurt Australia’s long-term living standards.

As Sydney’s median house price climbs by almost $850 each day, economists warn future wage increases will be lower because so much money goes into bricks and mortar holds back investment in businesses or lifechanging technological advances.

The Reserve Bank resumed cutting official interest rates in mid-2019 in a bid to get the economy expanding faster to drive down unemployment and push up wages growth. The advent of the coronavirus pandemic last year forced it to cut rates to a record low of 0.1 per cent while starting a quantitative easing program that has pumped more than $200 billion into the financial system.

Since it started cutting rates, the average mortgage to buy an established house in NSW has jumped from almost $554,000 to a record $755,000 in July, an increase of 36 per cent over two years.

The average mortgage has grown in every state and territory over that period. In Victoria, it has climbed by a third to $634,000, in Canberra it has increased by 28 per cent to $575,000 while across Queensland it is now $478,000 after lifting by 22 per cent.

The mortgages have been needed to deal with house prices that have soared, especially since the middle of last year.

Sydney’s median house price is now $1.3 million, a jump of $308,000 over the past 12 months, or $843 a day. Melbourne’s median house price, as measured by CoreLogic, is now $955,000 after increasing by $473 a day over the past year.

The big run-up in prices has resulted in the nation’s banks now holding a record $1.9 trillion in mortgages to owner-occupiers and investors. Loans to owner-occupiers have lifted by $145 billion in just two years.

It’s that leap in mortgages, being funnelled into the property market, that has economists worried.

RBC Capital Markets managing director Su-Lin Ong said a huge amount of capital was being driven into housing instead of more productive pursuits by low interest rates, government incentives and the tax system.

She said while construction was a key part of the economy, it did not employ as many people as the professional and scientific sectors.

Banks found it much safer, and easier, to hand over hundreds of thousands of dollars to people to buy an existing home rather than sinking it into a new business.

‘‘You can apply for a home loan on an app, but it’s a hundred times harder for an SME to get a loan,’’ she said. ‘‘From a bank’s point of view, it is a safer channel for lending. It’s a much higher risk profile to lend to business.’’

Ms Ong said if more money went into research and development or innovative companies, there would a long-term benefit to the country. ‘‘It’s a simple question of opportunity cost. What aren’t we doing because we’re putting so much money into housing?’’

Earlier this year, the Bank for International Settlements, which acts as the central bank to the world’s central banks, released research showing that while higher house prices delivered a short-term boost to economic activity via higher household consumption, longer-term productivity was actually lower.

In Australia, the Productivity Commission earlier this year found productivity growth in the decade to 2020 had fallen to its slowest rate in 60 years.

Stephen Anthony, chief economist with Macroeconomics Advisory, said without a lift in productivity, all Australians would suffer. ‘‘If you want living standards to improve, if you want wages to increase, then you need an increase in productivity.’’

Mr Anthony said both here and around the developed world, housing had become a Ponzi scheme that was being propped up by both central banks and governments.

He said with monetary policy totally exhausted, governments had to step up by putting in place policies that rewarded risk taking and ensuring all their spending was done with an eye to efficiency.

Source: Sydney Morning Herald